When my wife Grace wrote the Part 1 of Music and the Mysteries of the Universe in 2016, she described how our friend, the Swedish flutist and guitarist Per-Olov Sahl, saw music as a bridge between the visible and the invisible, between human breath and cosmic rhythm. Eight years later, this continuation follows Per-Olov on a pilgrimage through Spain, together with his old friend, the architect Lars Asklund, whose fading memory has transformed music into a language of remembrance. The project was a tribute to “the bird concert,” Concierto Madrigal by the blind Spanish composer Joaquín Rodrigo.

In Spanish poetry and folk music, birds symbolize the spirit of life, the wings of love, and God’s presence in nature. For the Spanish composer Rodrigo, birdsong was one of the most beautiful sounds he knew. He often claimed that birds were humanity’s first music teachers.

The Swedish flutist and guitarist Per-Olov Sahl says that in mysticism, the bird represents the soul flying upward toward God — and that both Rodrigo and the Spanish guitarist Andrés Segovia reveal this in their art.

Rodrigo lost his sight as a child but developed an inner vision through sound and tone. In his music, birdsong becomes an image of the freedom he lacked physically but experienced in his inner universe. For Segovia, music was not merely an expression, it was life itself. Both had a poetic relationship with the divine, and I mention this because the same spiritual force drives Per-Olov Sahl’s artistic understanding.

I have known Per-Olov for many years, and my wife Grace wrote an article about him in 2016 titled Music and the Mysteries of the Universe. At that time, we had just moved from Davao in the Philippines to La Herradura in Spain. Per-Olov was delighted that we had chosen to live in a place of great importance to Segovia. He visited us immediately together with his wife, Barbro, and spoke with excitement about the composer Rodrigo and the guitarist Segovia, both of whom he deeply admired.

He told us about Segovia’s close relatives who perished when ships of the Spanish Armada were smashed against the cliffs of La Herradura in a violent storm, and that the name Rodrigo can be traced back to southern Sweden, the region he himself comes from.

Per-Olov believes his attraction to Spain is rooted in something buried deep within him. He often says that music carries memory, that tones bear traces of journeys we do not consciously remember. Perhaps that is why he feels so at home in Spain, where the Visigoths once settled after their long migration from the north.

According to ancient chronicles, they left the North carrying with them a stern, Nordic longing into the Iberian sun. They brought their faith, their language, and their songs, and were transformed in their meeting with the Latin world. Their legacy lives on in Spanish art and architecture, as well as in the deep, melancholic beauty of Spanish music. It is as if Per-Olov follows this same ancient movement: from north to south, from cold to warmth, from the earthly to the spiritual.

He seeks not conquest but meaning: a harmony between human and mystery. He believes that both the Vikings and the Goths sought what people still seek today: a glimpse of order within chaos.

With this as his starting point, a few years ago, he decided to embark on a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela to gather impressions for an old dream, to record the “bird concerto,” Concierto Madrigal by Rodrigo, with himself as soloist on both flute and guitar.

He shared his plan with his old friend, architect Lars Asklund, who had developed severe memory problems after a hospital stay caused by Covid.

Once one of Malmö’s most celebrated architects, Lars’s life changed abruptly when he woke up one morning and could no longer tell the time. He had forgotten what the hands and numbers meant, along with much else we take for granted.

When the eighty-two-year-old architect heard about Per-Olov’s plans, he immediately wanted to join. He still felt physically strong, even though his memory had taken a serious blow. Per-Olov agreed right away. Earlier in his career, he had trained care workers who worked with dementia patients in how to use music as therapy, and he wanted his old friend to experience one final pilgrimage through landscapes they both loved.

It was the spring of 2024, and Grace and I were living in a small town in Galicia, about a hundred kilometers from Santiago de Compostela, where most pilgrimages end. Not because they planned to walk only that distance, but because they wanted to visit us first. Then they would continue via the lighthouse at Fisterra to Santiago de Compostela and on to Pamplona, where Lars Asklund had once run with the bulls in his youth, inspired by Hemingway.

Grace and I helped them create a Facebook page, Glada Bohemer (“Happy Bohemians”), where they could post pictures from the journey, but they never had time to update it. They were not trained in documentation and focused instead on undocumented experiences. Fortunately, Per-Olov took some photos with his phone, and I took a few myself when they visited us.

One of the reasons they wanted to visit us was that I had been a friend of the Norwegian poet Marie Takvam in the 1970s. She and Lars Asklund had once had a close relationship, and she was one of the people he still remembered. He brightened when I told him about my friendship with his old flame, and memories surfaced from the fog.

It is, of course, challenging to navigate life when much of one’s memory is gone, but Asklund’s good humor and positive attitude remained intact. And with Per-Olov’s habit of singing songs they both knew, they found a rhythm… a form of musical communication that made the journey possible.

When words disappear, music remains. Among people with dementia, tones live in the darkness… tones that still know who we are, even when we have forgotten ourselves. A familiar song can open a window to a lost landscape, and according to Per-Olov, music reminds us that the soul never becomes ill, only silent. He says that music’s deepest power lies not in technique but in its ability to awaken the living part of us, no matter how far into forgetfulness we have wandered.

Those interested in learning more about the journey can visit the Facebook page Glada Bohemer and contact Per-Olov Sahl, who will gladly share more about this remarkable adventure.

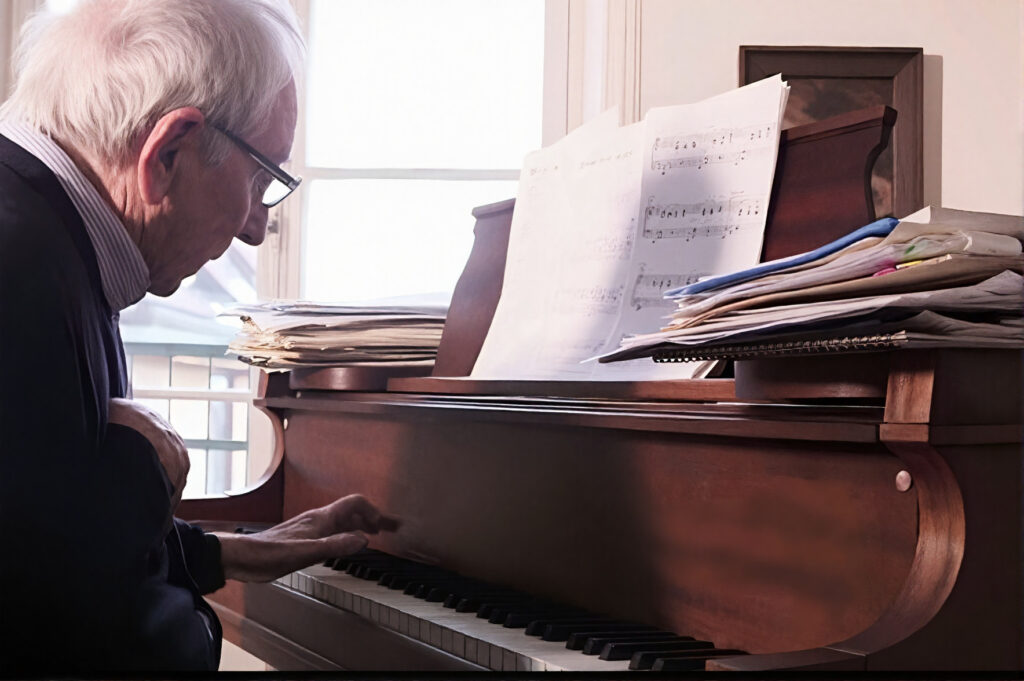

When the Swedish poet Tomas Tranströmer suffered a stroke in 1990, he lost his ability to speak. The right side of his body was paralyzed, words vanished, but not music. He continued to play the piano with his left hand, and in those simple tones, he found a new language, one without grammar, yet full of meaning. For Tranströmer, music became an extension of poetry, a place where thoughts no longer needed words. He wrote that “within every silence there is a door that only music can open.”

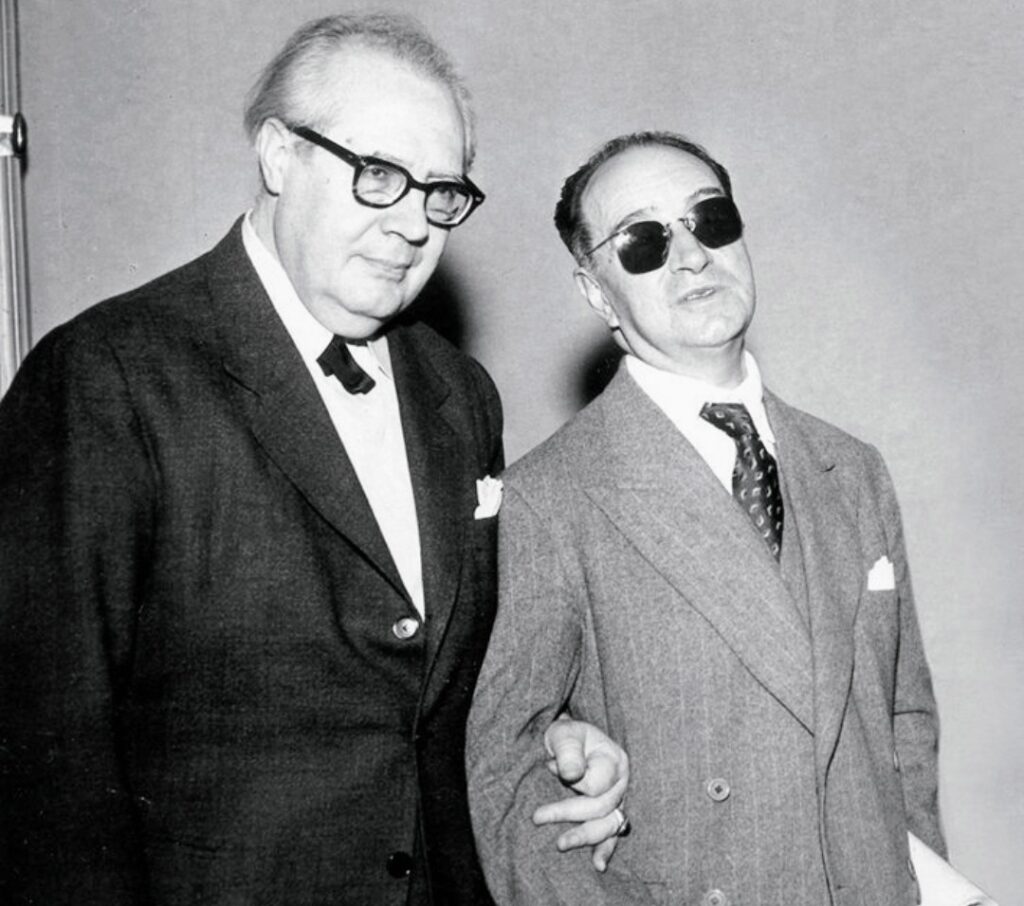

Per-Olov met Tranströmer a few years after his stroke through a mutual acquaintance, the composer Werner von Glaser. This opened a dialogue between them — Tranströmer at the piano, Per-Olov on flute and guitar — moments of shared sound that meant a great deal to both.

Music is more than tones; it can be a bearer of hope. It reminds us that what is caught in darkness can still sing freely in the light, regardless of the condition we find ourselves in on this earth.

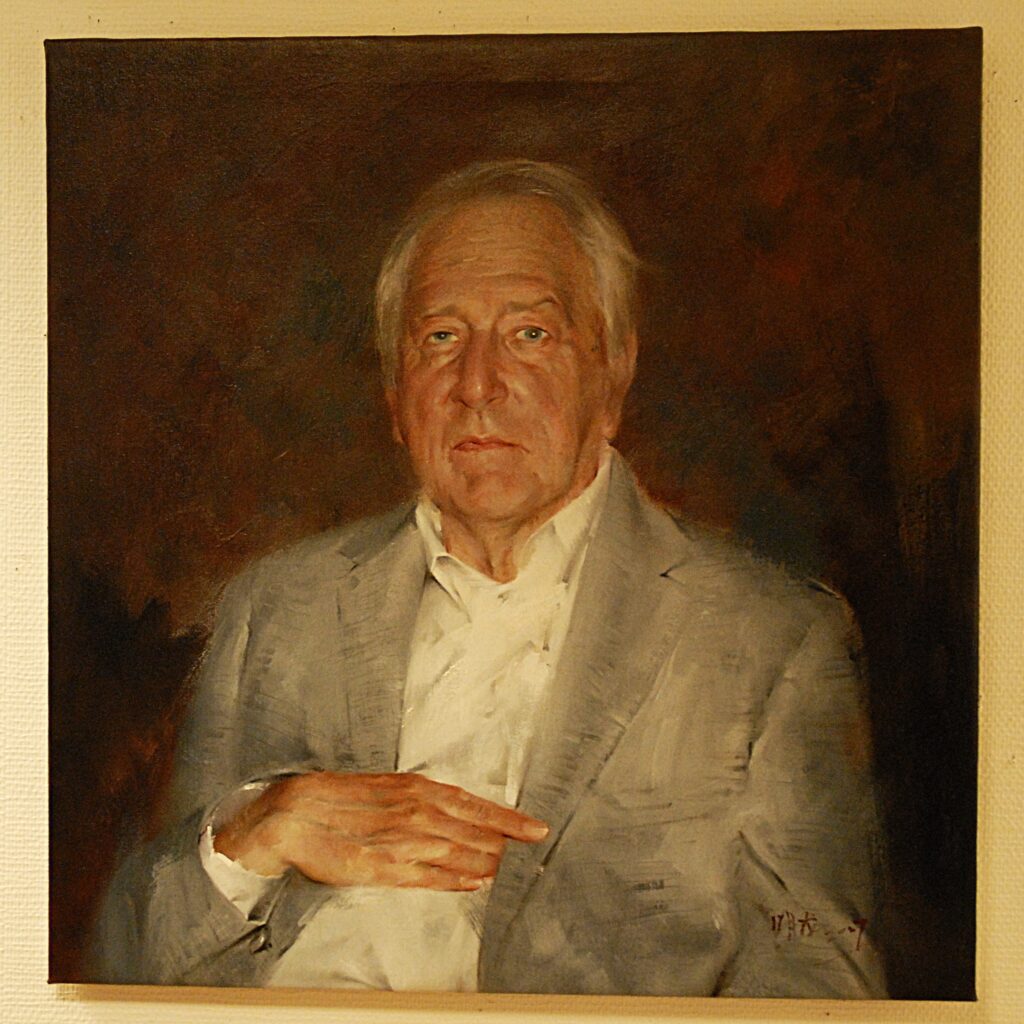

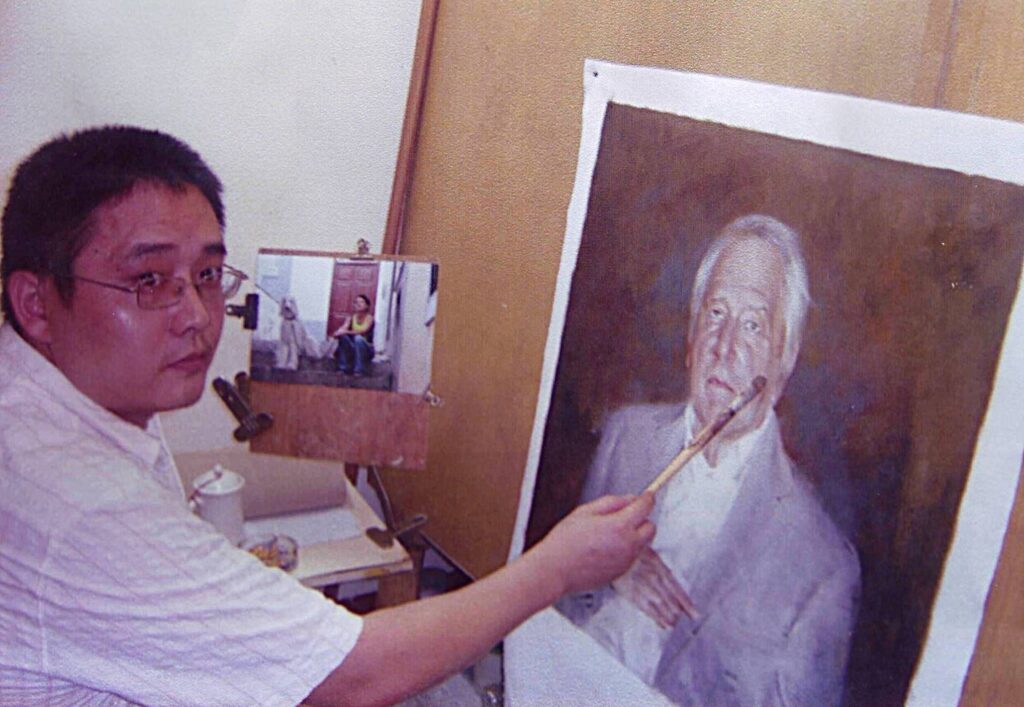

I later commissioned a portrait of Tomas Tranströmer in China by the portrait specialist Gui Ming Long.

The photo used for the painting was taken during a small concert and poetry reading at Ängsö Castle. Tranströmer had been invited, and Per-Olov performed guitar as a guest artist in an American ensemble that was visiting. I brought my video camera and documented the event. Some photos of the castle and its surroundings also became part of the project. This is the first time this short video is shown:

Featured image © Eldar Einarson